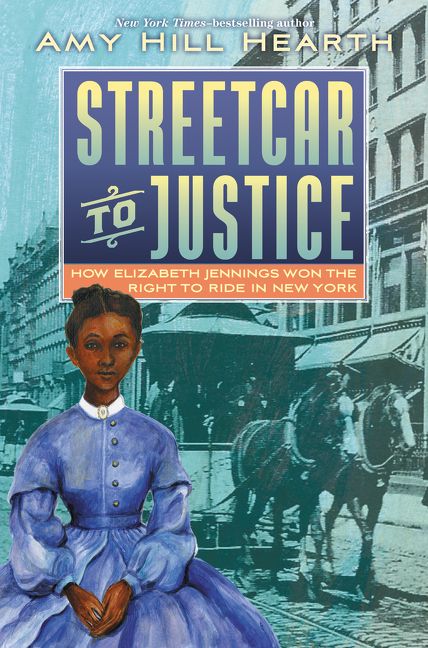

Streetcar to Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride in New York City by Amy Hill Hearth, 144 pp, RL 4

Streetcar to Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride in New York by Amy Hill Hearth is a compact, richly researched account of Elizabeth Jennings, the woman who refused to give up her seat on a streetcar in 1854, one hundred years ahead of Rosa Parks.

There are so many fascinating facets to the story of Elizabeth Jennings, but Hearth must set the scene for readers first, detailing the differences and similarities to circumstances and events from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, Hearth begins Streetcar to Justice with, "Three Notes about Language," informing readers that, while the word colored, "is not accepted today because it has evolved into a loaded word meant to be racist and hurtful," it was commonly used to refer to African Americans in Elizabeth Jennings's era. Hearth also lets readers know that the term civil rights is used mainly to describe the movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and she replaced it with equal rights for blacks to avoid confusion. Finally, she clues readers in to words used to define social class, an important aspect of Jennings's story.

There are so many fascinating facets to the story of Elizabeth Jennings, but Hearth must set the scene for readers first, detailing the differences and similarities to circumstances and events from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, Hearth begins Streetcar to Justice with, "Three Notes about Language," informing readers that, while the word colored, "is not accepted today because it has evolved into a loaded word meant to be racist and hurtful," it was commonly used to refer to African Americans in Elizabeth Jennings's era. Hearth also lets readers know that the term civil rights is used mainly to describe the movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and she replaced it with equal rights for blacks to avoid confusion. Finally, she clues readers in to words used to define social class, an important aspect of Jennings's story.

Jennings lived at home with her parents in New York City and was on her way to the First Colored American Congregational Church to play organ for choir practice. Hearth sets the scene thoroughly for the day of July 16, 1854, detailing everything from the challenges of walking in the dress of the time, the waste, filth and disease that crowded the hot, drought-ridden city with few sidewalks to the stray dogs, hogs (yes - wild hogs roamed the streets of New York City at the time!) and pickpockets. Anxious to get out of a dangerous situation and make it to rehearsal on time, Elizabeth Jennings, a respectable, genteel woman, determined to stop the streetcar meant for whites and hope that the conductor would be understanding and her and her friend ride. Instead, Jennings was physically, violently removed from the streetcar. Righting herself, she boarded a second time, at which point the conductor drove on until reaching a police officer who physically removed Elizabeth Jennings again.

Hearth details many fascinating aspects to Elizabeth Jennings's life (she started the first free kindergarten for Black children in New York City!) and her family. Her father, Thomas Jennings was a business man, patriotic American and activist, belonging to an impressive list of organizations and friends with many influential people, including Frederick Douglass, who wrote a tribute to Jennings after his death. Amazingly, it was newly minted attorney Chester A. Arthur, who would become the twenty-first president of the United States, who took on the case, Elizabeth Jennings v. Third Avenue Railroad Company. Rather than pursuing a criminal case, a civil case was filed in the hopes that a win would result in financial damages that might end segregation by the Third Avenue Railroad Company rather than risk further costly lawsuits in the future.

Facing a room full of white men, including the jury that had to determine whether Jennings was telling the truth when recounting her experience, she won and the owners of the Third Avenue Railroad Company moved quickly to integrate their cars. While the story of Elizabeth Jennings and her important civil law suit is a vital part of American history, it is possibly unknown to many because it occurred in an era before modern media and also because the majority of newspapers in the nation were focused on a more pressing issue at the time, slavery. Yet, books like the highly engaging Streetcar to Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride are so important, especially in this time when the Souther Poverty Law Center reports that U.S. education on slavery is sorely lacking for a number of reasons.

Hearth provides much documentation and evidence in Streetcar to Justice with a bibliography, notes, author's note, further reading, historical timeline, important locations, illustrations and index, sharing with readers how a "creepy old house" led to the writing of this book. Living near a house might have been the summer home of Chester A. Arthur, Hearth began researching him, eventually uncovering information about his early years as a lawyer with a special interest in equal rights cases for Blacks. Hearth even retraces Jennings's steps, ending her book with these important words,

Too often, we thinking of history as a permanent series of events. The reality is that stories form the past are often forgotten. Much depends on who remembers and tells the stories form the past and how they are told. The contributions of Black Americans, other minorities, and women have been overlooked, often deliberately. Too quickly, we conclude that is an event is not already in an official textbook, it didn't happen or it's not important. The story of Elizabeth Jennings reminds us that this is not so. Sometimes, interesting stories are right in front of us, if only we take the time to look.

Source: Review Copy