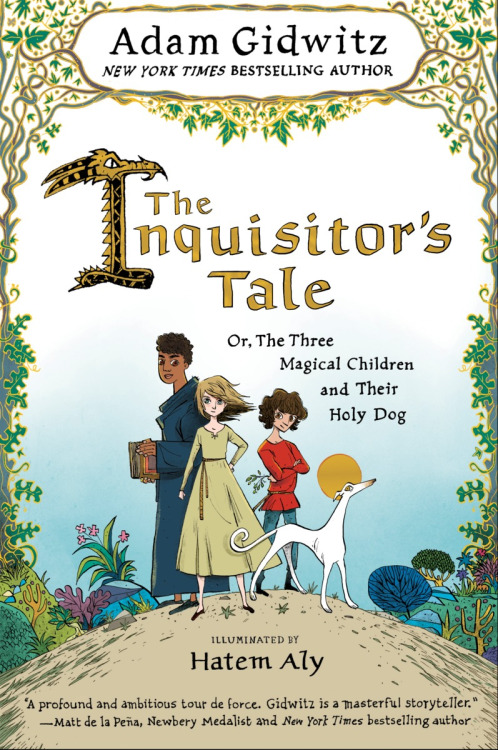

The Inquisitor's Tale, or Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog by Adam Gidwitz, illustrated by Hatem Aly, 384 pp, RL 4

In 2010, A Tale Dark and Grimm the debut novel by Adam Gidwitz, captured my attention and that of many other readers, young and old. Gidwitz is a master story teller and his reworking of the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, many of them less than well known, is marvelous. I was thrilled when my son shared my enthusiasm for this book and even more excited when I discovered that reading it out loud was a great way to entice my students, many of whom are reluctant and/or struggling readers, to persevere with a longer book. True to his story telling nature, Gidwitz is back with The Inquisitor's Tale, a manuscript illuminated by Hatem Aly and like no other children's book I have read before.

Set in 1242 and echoing the structure of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, The Inquisitor's Tale finds an (initially) unnamed narrator at the Holy Cross-Roads Inn, a day's walk north of Paris. It is the perfect night for a story as a group gathers around the rough wooden table, sticky with ale. The king will be marching past the inn on his way to war with three children and their dog. A brewster, a librarian, a nun, a butcher, a jongleur, a chronicler, a troubadour and the innkeeper take turns telling stories of these three children and their dog, each one adding to the tapestry of their story. Subtly but surely, Gidwizt presents characters who are discriminated against or (much) worse, for gender, religion, and class.

Set in 1242 and echoing the structure of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, The Inquisitor's Tale finds an (initially) unnamed narrator at the Holy Cross-Roads Inn, a day's walk north of Paris. It is the perfect night for a story as a group gathers around the rough wooden table, sticky with ale. The king will be marching past the inn on his way to war with three children and their dog. A brewster, a librarian, a nun, a butcher, a jongleur, a chronicler, a troubadour and the innkeeper take turns telling stories of these three children and their dog, each one adding to the tapestry of their story. Subtly but surely, Gidwizt presents characters who are discriminated against or (much) worse, for gender, religion, and class. Jeanne is a peasant girl who is seized with visions of the future. As an infant, her parents killed her babysitter/protector, Gwenforte, a white greyhound with a copper blaze on her snout, thinking that the dog had attacked Jeanne. Far from the truth, the loyal Gwenforte had saved the baby from an adder that made its way into the house. Realizing their mistake, they gave the dog a proper burial in a grove that quickly became a holy place and the dog thought of as a saint. Years later, after seeing a beloved neighbor, thought to be a heretic, hauled off by a huge, fat, red headed monk from Bologna, Jeanne knows she must keep her fits and the visions that follow a secret. She must also keep Gwenforte, who has come back to life, a secret.

Jeanne is a peasant girl who is seized with visions of the future. As an infant, her parents killed her babysitter/protector, Gwenforte, a white greyhound with a copper blaze on her snout, thinking that the dog had attacked Jeanne. Far from the truth, the loyal Gwenforte had saved the baby from an adder that made its way into the house. Realizing their mistake, they gave the dog a proper burial in a grove that quickly became a holy place and the dog thought of as a saint. Years later, after seeing a beloved neighbor, thought to be a heretic, hauled off by a huge, fat, red headed monk from Bologna, Jeanne knows she must keep her fits and the visions that follow a secret. She must also keep Gwenforte, who has come back to life, a secret. The second child is William, an oblate. The son of a great lord fighting in Spain against the Muslim kings and a Saracen from Northern Africa, he was left at a monastery as a baby. More than his dark color, the size of William is a constant source of amazement and occasional frustration - or worse - to the monks. William's great size, strength and appetite, both for food and knowledge, make him a threat to some of the monks and he is sent away with a donkey, saddlebags full of books to be delivered to another monastery by way of a forest inhabited by fiends.

The second child is William, an oblate. The son of a great lord fighting in Spain against the Muslim kings and a Saracen from Northern Africa, he was left at a monastery as a baby. More than his dark color, the size of William is a constant source of amazement and occasional frustration - or worse - to the monks. William's great size, strength and appetite, both for food and knowledge, make him a threat to some of the monks and he is sent away with a donkey, saddlebags full of books to be delivered to another monastery by way of a forest inhabited by fiends.  Finally, there is Jacob, a Jew who survives the burning of his village by Christian boys and has the ability to miraculously heal the sick and injured. Jacob only wants to be reunited with his parents, but his ability to read and his love of his religion shape his path. As The Inquisitor's Tale unfolds, it becomes clear that, not only is this a story about stories and storytelling, it is a story about books. There are many strange twists and turns in The Inquisitor's Tale, including a hilarious incident with a dragon who, by way of a lactose intolerance issue, comes to pass gas that sets knights on fire. This leads to a fantastic scene with a cure from Jacob that involves vomiting up a tremendous amount of French cheese, Époisses, which Jeanne describes as tasting like life, "Rotten and strange and rich and way, way too strong." As the tales are told, we come to learn that King Louis is planning a book burning that the children will inevitably be part of. In fact, he has had his monks gather up all the texts written in Hebrew and created an enormous bonfire in the heart of Paris. Being an oblate, William has a deep reverence for books, knowing the time and effort that goes into copying out a text. Being Jewish and able to read, Jacob also has a great reverence for books and the word of the Talmud. It is this reverence for books that leads the three children and Gwenforte to an amazing standoff with the king and his terrible mother at Mont Saint-Michel, the incredible island commune in Normandy.

Finally, there is Jacob, a Jew who survives the burning of his village by Christian boys and has the ability to miraculously heal the sick and injured. Jacob only wants to be reunited with his parents, but his ability to read and his love of his religion shape his path. As The Inquisitor's Tale unfolds, it becomes clear that, not only is this a story about stories and storytelling, it is a story about books. There are many strange twists and turns in The Inquisitor's Tale, including a hilarious incident with a dragon who, by way of a lactose intolerance issue, comes to pass gas that sets knights on fire. This leads to a fantastic scene with a cure from Jacob that involves vomiting up a tremendous amount of French cheese, Époisses, which Jeanne describes as tasting like life, "Rotten and strange and rich and way, way too strong." As the tales are told, we come to learn that King Louis is planning a book burning that the children will inevitably be part of. In fact, he has had his monks gather up all the texts written in Hebrew and created an enormous bonfire in the heart of Paris. Being an oblate, William has a deep reverence for books, knowing the time and effort that goes into copying out a text. Being Jewish and able to read, Jacob also has a great reverence for books and the word of the Talmud. It is this reverence for books that leads the three children and Gwenforte to an amazing standoff with the king and his terrible mother at Mont Saint-Michel, the incredible island commune in Normandy.

While The Inquisitor's Tale has a deep vein of Christian thought and history running through it, Gidwitz makes his story richer and more engaging by also highlighting those who suffered in the face of Christianity. He begins the book, which he researched for six years and includes an extensive and interesting author's note as well as an annotated bibliography, with a quote from poet W. H. Auden that calls for loving "your crooked neighbor / With your crooked heart." It is this thought, one that Jacob reads in the Talmud and Jeanne notes that Jesus said, but in reverse, that drives the story and the children. As their adventures escalate and they meet many broken, crooked, questionable adults (they are the only children in the story) and they forgive and love their neighbors over and over. When they find themselves discussing Cain, Abel and the use of the word "bloods" (and not "blood," which William attributes to drunk scribes) they compare the loss of one life, which is really the loss of many - the descendants that person may never have - to the loss of books and the knowledge they contain and can eventually touch many lives with, Willam saying,

A scribe might copy out a single book for years. An illuminator would then take it and work on it for longer still. Not to mention the tanner who made the parchment, and the bookbinder who stitched the book together, and the librarian who worked to get the book for the library and keep it safe from mold and thieves and clumsy monks with ink pots and dirty hands. And some books have authors, too, like Saint Augustine or Rabbi Yehuda. When you think about it, each book it a lot of lives. Dozens and dozens of them.

To this, Jeanne adds, "Dozens and dozens of lives, and each life a whole world." Having worked in almost all aspects of the world of kid's books at this point in my working life, I feel compelled to add to this idea. It is truly amazing, even in this day when books are printed by machines and illustrations can be created on computers, to realize how many hands touch a written work before it becomes a book on a shelf, from the literary agent (and the agent's assistant) to the editor at the publishing house to the booksellers, reviewers and librarians who embrace the story and pass it on, retelling it to invite new readers. And that's not even mentioning the writer's critique groups and family and friends who read manuscripts in the early (and late) stages. Storytelling touches us all, whether we write the words or not, and I am grateful to Adam Gidwitz for reminding us of this - especially with such a highly entertainingly readable book like The Inquisitor's Tale!

source: review copy