(Still) Thinking About Diversity in Kid's Books

A couple weeks back, I listened to an interview with Angie Thomas, author of The Hate U Give, about her new book, The Come Up, on It's Been a Minute with Sam Sanders. It is a great interview (her mom even weighs in at one point) but she said something that I couldn't stop thinking about. Thomas mentioned that, while she was finishing edits for her first book and thinking about sending it out to literary agents, she heard a statistic stating that there were more kid's books featuring trucks and animals as main characters than Black kids. A week or so later, reading Marley Dias's Marley Dias Gets It Done and So Can You! and thinking about her #1000BlackGirlBooks campaign, I wondered if she was trying to collect 1,000 books with Black girls as the main character or just 1,000 books total. Are there actually 1,000 different kid's books with Black girls as the main character? Yes! There are, and you can find them here!

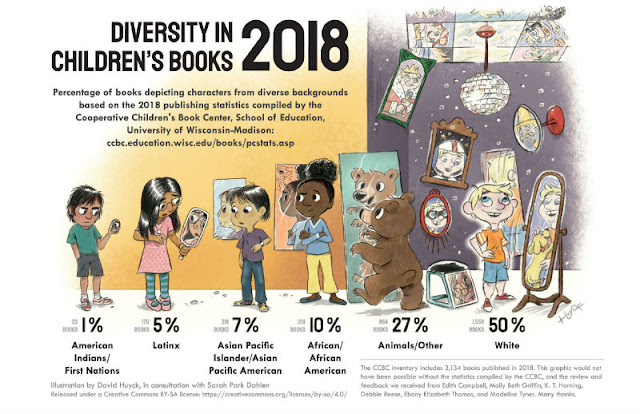

And then I fell down a rabbit hole of statistics about representation and diversity in kid's books. These numbers weren't new to me. I have been following the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign since it started in 2014. This issue and seeking out books for review with diverse characters (although, to be honest, more Latinx than anything else, since that is the majority of my students I work with are Latinx) occupies a lot of my thinking about kid's books. What surprised me is that the numbers - both of books being published with diverse characters and being written and illustrated by people of color - have changed only incrementally over the last few years.

|

| infographic by Tina Kügler |

|

| inforgraphic by David Huyck, in consultation with Sarah Park Dahlen and Mary Beth Griffin |

The Cooperative Children's Book Center School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison started keeping statistics about the number of books created by Black authors back in 1985 when the then director of the CCBC was serving as a member of the Coretta Scott King Award panel and was appalled to learn that there were only 18 titles eligible for the award. The CCBC does not include a copy of every single kid's book published every year in their numbers. However, they do receive, "most, but not all, of the trade books published annually in the United States by large corporate publishers. The CCBC also receives books from some smaller trade publishers of series or formula non-fiction books published here. We also receive books from several Canadian publishers that distribute in the United States. Most recently, we've begun receiving a small number of books distributed by a few U.S. trade publishers with a U.S. price label, but not in a U.S. edition. We also receive a small number of independently published and self-published books."

A recent article on Bustle does a good job breaking down the data the CCBC and Lee & Low Books, the largest multicultural children's book publisher in the United States, have been collecting. Lee & Low also have a fantastic blog, The Open Book Blog: A Blog on race, diversity, education, and children's books. In fact, in 2015, Lee & Low embarked on an impressive survey of the publishing industry itself to determine the amount of diversity among publishing staff. You can see the results of that study here, although I'm sure it's no surprise that publishing is overwhelmingly white and female, across all levels. Interestingly, while poring over the list of participating publishers and journals, I did not see HarperCollins or Simon & Schuster among the participants. Lee & Low are conducting a new survey this year and I can't wait to see the results.

So, what does this mean? What do we do next? Why aren't there more POC working in the publishing industry? And why aren't there more writers and illustrators of color being published? As an elementary school librarian, I tell my students every day that I want at least one of them to grow up and write the Latinx Junie B Jones or Latinx Magic Tree House series that will be on shelves for decades and be a rite of passage for all emerging readers. As Marley Dias says,

How can educators expect kids to love, instead of dread, reading when they never see themselves in the stories they're forced to read? Since most kids have to go to school, being in class every day can be a way to give kids hope - or the opposite, if a teacher or school doesn't see that all kinds of books an experiences are important. If there are no Black girl books as part of the school curriculum, then how are we expected to believe that all that stuff teachers and parents are constantly telling us about how we're 'all equal'? If we're all equal, then we should all be represented equally. If black girls' stories are missing, then the implication is that they don't matter. I didn't like it so I had to do something.

In her interview with Sam Sanders, Angie Thomas worried about every book by an author of color having to be an important issue book. As she said, and this feels like the right place to end, "can we get a Twilight featuring Black kids? You know, can we get romantic comedies featuring Black kids, rom-coms? Can we just have stories with them just being and just doing? Can we get even crappy books about black kids?"